Hampshire HistBites

Hampshire HistBites

War Reaches Hampshire: Catastrophe in the Cathedral

One day, the halls of Winchester Cathedral are filled with whispered prayers and holy songs. The next, they echo with the roaring of gunfire and hooves crashing over the tombs of holy men.

The English Civil War was a conflict that spared neither the lowest of peasants nor the highest of kings. It was only a matter of time before the winds of war reached Winchester. In this episode, listen to a 'firsthand' account of the damage caused to Winchester Cathedral and the impact it had on the city.

Alex Beeton, a third-year PhD student at Oxford University studying early modern British history, talks about the history of the English Civil War and the fascinating stories of the people involved.

If you want to find further information on this episode or to listen to other episodes of Hampshire HistBites, visit our website.

War Reaches Hampshire: Catastrophe in the Cathedral

Intro: Welcome to Hampshire HistBites. Join us as we delve into the past and go on a journey to discover some of the county’s best and occasionally unknown history. We’ll be speaking to experts as well as enthusiasts, asking them to reveal some of our hidden heritage, as well as share with you a few fascinating untold stories.

Julie: Rescued manuscripts, civil unrest and damage to Winchester Cathedral. Do you know what the link is?

Hello and welcome to this week's episode of Hampshire HistBites. My name is Julie Dypdal and I'll be your host for this episode in which we'll explore the Civil War in Hampshire. In a few minutes, we'll hear from Alex Beeton, who is a third year PhD student in early modern British history, who can give us an overview of the campaigns in Hampshire, between Oliver Cromwell, parliamentarian, and the Cavaliers who wanted to preserve the monarchy and the rule of King Charles I. But first we're travelling through time to Winchester in 1665, where Aisha Al-Sadie finds out what happened on one of the most dramatic days of the war for the city's cathedral.

Aisha: Today's date is the 14th of December 1665, and we are remembering the plight of the people of Winchester and their cathedral at the hands of William Waller and his soldiers during the Civil War. It is exactly 23 years since that day, lots of damage was done to the cathedral and its contents. And over the last few days, Parliament has returned the Winchester Bible, 15 manuscripts, and some 200 printed books have been given to Winchester College and much of the church plate has been returned, but let's find out what happened on that day 23 years ago. I have with me an eye witness who was there during the attack in 1642. Hello, can you please tell me what you saw?

Man: I was in the cathedral around 9:00 AM, tidying up after morning Eucharist. Suddenly I heard shouting echoing around the building. I ran towards the nave and saw a huge number of armoured men carrying pikes rushing through the west doors of the cathedral shouting "cry havoc". I then realized that some of them were also on horseback, here in the cathedral, riding their horses in God's house! Their colours were flying, drums beating, guns already primed and ready to shoot. I was terrified.

Aisha: Wow. That must have been truly terrifying. What did you do next?

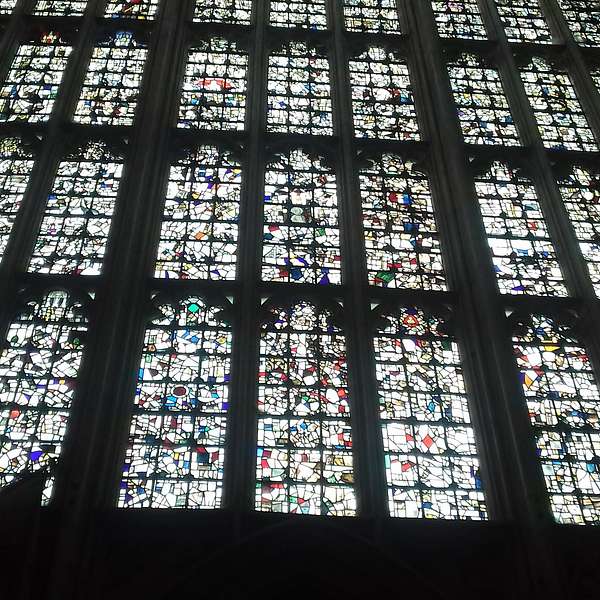

Man: Well, as I watched from my hiding place, they ran up to the choir screen. The horsemen were forced to dismount and they fired their guns and cut their swords on the statues of King James VI and King Charles I on the new stone choir screen, all while swearing that they would capture Charles and bring him to Parliament to answer for his crimes. They even tried to burn the statues! Then they shot their muskets at the great West Window, smashing all the glass, which fell like coloured rain onto the stone floor. That was one of the biggest blows as it had only been repaired three years ago.

Aisha: How awful! Did they then leave?

Man: No, no. Then they went into the Choir and caused lots of damage to the stalls, broke the altar, the organ, and they picked up the communion rails, the singing books and the books of Common Prayer and burnt them. They also burned the wooden figures of Henry Beaufort from his Chantry chapel. Then they climbed up on top of the Presbytery screen and pushed the mortuary chests down onto the floor. They made such a massive noise. The lids were forced open and the bones of Anglo-Saxon Kings, a Queen and Bishops, had been laid to rest, were desecrated, thrown through windows like common stones, such disrespect to our heritage.

Aisha: Surely after that they were satisfied and left. What else could they do?

Man: That's what I thought but unfortunately not! After that, they went up into the muniment room.

Aisha: Oh no.

Man: Yeah. Yeah. John Chase our librarian tried to stop them, but he's not a soldier. They took irreplaceable ancient documents, books, Saxon charters, rolls and charts and burnt them. Threw them into the river or made them into kites. Tougher the butcher told me that some of the soldiers brought some of the sheets into a shop to wrap up their meat. They've got no respect for our history, all that knowledge gone. Some of the brothers at St. Cross, just down the river, managed to fish some of the manuscripts out of the water and will return them to us but the majority of them are lost.

Aisha: Am I right in thinking that, that wasn't the end of the attacks on the cathedral during the Civil War?

Man: That's right. We were attacked another four times. In the later attacks on the City, Winchester Castle was destroyed and the people were forced to share their homes with the soldiers and their horses, even though all their furniture and belongings had been taken away from them. The buildings around the Cathedral were sacked. Bishop Walter Curle escaped before the soldiers reached the city, but many of the clergyman weren't so lucky and were hanged, and many drawn and quartered. Lots of fine things were also stolen and sold, including the Winchester Bible.

Aisha: The Winchester Bible that was commissioned by Henry of Blois in the 1100s, that, that Winchester Bible? What happened to it?

Man: I'm not sure, but Parliament gave it back to us under the order of Cromwell.

Aisha: I believe that the people of Winchester then tried to get help. Is that right?

Man: Yes. The people of Winchester then wrote to King Charles for support and money. We had always sent him money for his campaigns whenever he asked, but instead of help, he sent us a picture of himself!

Aisha: So what happened next?

Man: The Cathedral was used as a stable for the troops horses and was in such a bad state of repair that four years ago Parliament actually wanted to demolish it.

Aisha: What!– really!!

Man: Yep. Luckily, the mayor managed to raise a petition to save it and use it as a meeting space. But unfortunately the money couldn't be raised to repair the roof. It was then used as a brew and malt-house.

Aisha: So it wasn't used as a church for a long time?

Man: That's right. Yeah. The last major event that the city played in the war was that the King stayed overnight in Winchester on his way to his trial in Windsor.

Aisha: Wow. I bet that must've been a really historical moment.

Man: Yeah, the Mayor, Aldermen and townspeople all came out and gave him the honour and the ceremony he deserved before he was dragged off to London and beheaded on the 30th of January 1649.

Aisha: A lot of good, all that death and destruction did. Now we have his son, Charles II as king anyway.

Man: That's very true, but the mark's been left on the City and the Cathedral, even though it has been restored as much as possible. The Dean and Chapter have been restored. A new organ has been purchased. Parliament returned a few of the manuscripts and books, and they did give us back the Winchester Bible, like I said,

Aisha: I'm glad that no further damage was done.

Man: So am I. Much more could have been done if it hadn't been for the brave actions of Nathaniel Fiennes, even though he was a Colonel in the parliamentary army, he protected the Chantry Chapel of Bishop William of Wickham, which the soldiers wanted to damage. I believe Nathaniel went to Winchester College, which Wickham founded, you see. Apparently he stood with his sword drawn defying, his own troops.

Aisha: Wow. That was really brave.

Man: Yeah. Yeah, it was. Anyway, best be off. Got to get ready for the next service.

Aisha:Thank you so much for your time.

Julie: That was an imagined account created by Winchester Cathedral learning officer Aisha Al-Sadie, with Ian Aston playing the part of the soldier, describing the Roundheads’ attack on Winchester Cathedral in 1642. But how does that event relate to the rest of the Civil War in Hampshire? Let's turn to Alex Beeton to learn more.

Alex: The Civil War in Hampshire really mirrors the Civil War in England. So what we're talking about is a, a war between the king and his Parliament, the king being Charles 1st, which broke out in 1642.

The reasons are way too many to go into in a, in a sort of, fairly short answer. So let's just say they're very big they're things like religion, the things like the relationship between king and parliament over who has more power, there's economic tensions and social tensions. Some people like to think that the Civil War kind of almost happened by accident, that there was a sudden outburst of short-term events, which basically kicked off a big ball - the biggest of which was a big rebellion in Ireland in 1641.

So once the war breaks out due to these very, very big reasons, the standard way of raising the armies is that each county or each side has their supporters around the country and bar very, a few small areas of England, mainly sort of congregated around the Southeast and Essex, which are very firmly for Parliament, most of England is in this large, this large wall with lots of ebbs and flows where one side will predominate for a while, then the other side will take back what they've, they lost the previous year. And Hampshire is very much falls into that pattern of an ebb and flow where the Parliamentary side, Royalist side trade ground each year.

Julie: Okay. So there's lots of tensions, not just in Hampshire, but all over England and as any conflict, basically, it's not – it might seem sudden, but it's not. It's just in the background for a lot of people, isn't it? So we also heard from the eyewitness account that Winchester Cathedral had quite a role and there was lots of destruction. Can you tell us a bit more about the destruction in Hampshire or maybe involving the cathedral or anywhere else around?

Alex: Yeah, sure. So just perhaps starting, they both acquire lots of stories and evidence, and so perhaps just splitting them up so I don't ramble for too long. But the Hampshire scenario is very interesting because being caught in between these two conflicting sides and the land having been traded back and forth, there is this regular, almost seasonal, course of destruction and misery. Most of the Civil War doesn't really involve big battles. There are a few very, very big battles, but most of the time we're talking about what we'd consider fairly small scale skirmishes, raids, basically lots of little, little miseries on a daily level. And the big killer it is more disease and the biggest problem is more a destruction of property, but also financial ruin caused by taxation.

So this is a period where there is a huge amount of very, very heavy taxation, especially by Parliament to pay for their armies. Ironically, one of the things Parliament had gone to war about had been excessive taxation imposed by the King. So a bit of an irony of fate.

In Hampshire, we do have lots of, as with so much of the country, there as these stories about the various types of destruction which take place. There’s a petition from a tenant of Winchester College called Anne Seal who writes in her petition asking for laxity with her payment of rent, that she had a very miserable time during the Civil Wars, that royalist soldiers under the commander, Ralph Hopton came and took 100 of her sheep, lots of her goods, frightened her. Then came some more soldiers under someone called Sir William Bedford and all the while she had to pay taxes to not just the royalists, but also the parliamentarians.

An anecdote I really, I really enjoy is William Ogle, the royalist commander of Winchester castle was asked to surrender to the parliamentarians or else they’d burn his house down in Stoke Charity, to which Ogle replied, he didn't really care if they burnt that house down because it actually belonged to his wife, not him.And as for the threat of there being a fire in the area, he said, if you please to burn the City, it would make a very spacious, fair garden for the castle”, which is where Olge was.

So, lots of violence and lots of destruction is going on in Hampshire and there are some big, big sort of acts of violence, but what we're talking about more is a lot of individual ruin really for, for individuals and the permanent threat of plague being spread by these armies. We have, a statistic I think is something along the lines, one in 10 adult males in Britain dies during the Civil Wars, mostly of plague, not really of battles.

And yes, like I said, really, we're talking about a very, very long running series of small campaigns rather than big battles. The biggest in Hampshire is probably at Cheriton in 1644 and maybe one or two other incidents, such as a siege of Basing House, just outside well in modern day, Basingstoke.

Julie: Wow. It's quite a lot of people though, one in 10, as in like modern day, it's actually more disease than battle, which is quite an interesting comparison, so to speak.

Alex: I also, I think it's important to remember as well, of course, that lots of these - I think one of, one of the problems we're thinking of is it's probably quite dangerous to think of the effects of Civil War purely in death, because we're also talking about a huge amount of forced change to people's lives like displacements of people, forced migration. One of the more interesting, interesting sources for this I've seen has been the examples of charity being given to soldiers who are in Hampshire, who want to get back to their homeland or home town. So there's, I think there's an example of a soldier asking for money at Winchester College in 1640s because he's he wants to get back home to a small village, I believe in Dorset. So you do have this huge, displacement of people, especially from Ireland due to the Irish rebellion, where lots of Irish Protestants come to England to try and get away from the war in their own country.

So alongside this huge decimation of – literal decimation – of the English population there is also this massive, massive displacement of people and change of circumstance.

Julie: So you already mentioned a few stories, but how did the community respond during this time?

Alex: Well, obviously we, we have to face problems with the evidence of the Civil War period because we do have a huge amount of fragmentary evidence but we don't have a huge amount of what we call very thorough evidence relating to how ordinary people and ordinary communities survive. We have more sort of these little fragments here, and little fragments there we piece together. But, in terms of responding to the Civil War itself, a lot of it was, was trying to make do in a very changed world.

And one thing which have increasingly come to think in recent decades has been that actually people were far better at cooperating and working together than previously thought. There was far more willingness to rub shoulders with enemies from the Civil War after the event. And most people were quite happy to focus on fighting against common enemies, such as religious radicals. So this is a period where everyone's terrified of religious radicalism. These are usually small, very vocal sects who are often have quite left - what we think of as left wing tendencies, such as the Diggers or Levellers who wants to transform society. So people respond in a very varied way, but there's a lot more in terms of, down, down to, earth responses and, and cooperation than we previously thought.

Julie: Yeah so ordinary people, although we can't really know for sure because of the evidence that survives, we can imagine that ordinary people, they did have a response. They did get very much involved, because it did affect them, obviously. But there was also lots of disrespect for history and heritage, lots of manuscripts got thrown in the river and so on.

Can we see any of this disrespect of history and heritage in Hampshire today? Are there any visible evidence from the Civil War?

Alex: Sure. Yeah, it's important to understand why the destruction of objects of heritage, historical things took place. So a lot of the time these types of destructions, weren't seen as a lack of respect for heritage, but actually in some interesting ways, seen as trying to return things to a much purer, older, form. So a lot of the destruction during the Civil War and I mean, deliberate destruction rather than destruction caused by the battles or for military endeavours, but deliberate destruction tended to be of a religious nature. So what's usually termed iconoclasm. That is the destruction of – well icons, but it has a looser meaning, meaning the destruction of religious objects. So statues, windows and so on.

Now, Parliament and Parliamentarians tended to take on iconoclasm is actually a very interesting thing where in Cambridgeshire and especially in Cambridge, Parliament had an iconoclast chief who was given this weird roving role to go around Cambridge colleges, especially and destroy all the icons he could find. His name was Dowsing, William Dowsing, I think. And he left a diary of his record of iconoclasm, where he would go from college to college, what he'd found destroyed.

So you do get a lot of iconoclasm during the English Revolution but it's important to remember that it's not necessarily due to a dislike of heritage. It's usually due to a very specific religious motive, which is, to return the English church to a purer form, stripped of religious icons. A specific type of Protestantism in this period of history, specifically thought, had been introduced by superstition. They were remnants of Catholicism and they had been reintroduced subtly by King Charles I. Charles I's Archbishop of Canterbury, William Lord. So in getting rid of these things, these parliamentarians think that they are obeying a religious instruction and returning the church to something far more approaching what had been case in the days of the Apostles.

So in a way it's not really dislike of heritage. It's more, dislike of what has been seen as bad new stuff introduced on us.

Julie: Yeah, absolutely. Because the term heritage is quite, it's relatively, quite new and it changes all the time, but it's quite interesting that they had this iconoclasm chief going around, like smashing windows.

Why? Well, I really want to read that diary ’cause that sounds fascinating. But about smashing windows because the west window in the cathedral in Winchester actually got smashed as well. And I think today they've restored that window using those smashed pieces, but they haven't put it back together into the original, oh, what's the word? Original shape. So it's just, it's a remnant of the Civil War saying it got smashed, but it's, it's still here. We're still using it. It's still here, which I think is actually quite beautiful.

Alex: No, I agree., I think the West Window is a really stunning monument to that period of history.

As I think we were talking a bit about earlier, the story of the Cathedral, is a really important example of iconoclasm. And it was an example of these types of things. So, to set the scene a bit, what Winchester cathedral’s treatment during the Civil Wars happened during one of these ebbs and flows where Parliament had the upper hand, Parliament managed to get control of the City. And basically they lost control of the troops, being a soldier in the early period is extremely miserable and commanders had a really, really tough time trying to stop their troops from, making up for the, the days of marching and deprivation by going looting.

So commanders tried to be quite strict to stop this and they also have to pay their troops very well to stop this, and what happened in the case of Winchester was the commanders lost control of their troops and their troops went on a rampage effectively, looting houses and the Cathedral Close and entering the Cathedral and basically indulging in a real bout of iconoclasm. So it might, it might be useful to kind of work our way from, as you enter into the Western west end of the nave, and then sort of make our way through the Cathedral as the soldiers did. So the soldiers break in, at least some are riding horses. This is a very classic Roundhead motif for cathedral bashing, which is to ride your horses in and sort of show that you, you think these, these cathedrals are sort of homes of, of pseudo Catholicism, that they are too ornate, that they're leading people away from true type of devotion to God, which is much more quiet, personal, low key to use a modern term. They begin, they begin to smash up the Western window either through, through shooting at it or throwing bones through it – I’ll get to the bones in a second. But any case the Western window gets destroyed. there was also a legend that Cromwell fires a cannonball through it which is possible but it doesn't seem likely. But in any case, the window seems to have been destroyed. Then their attention turns to the statues of King James and King Charles, which are still underneath the Western window and if you look closely at, I believe it's the robe of King James, you will see behind his leg there is a hole which is from a musket ball fired by the soldiers through it. After roughing up the statues, they then proceed down the nave where effectively, I guess they just have fun really, as soldiers let loose, will do, which was, they just break stuff. If they find anything nice, they steal it and they caused a lot of destruction to the Cathedral.

And I think it's very important to remember these again, I'll reiterate, the life of life of soldiers during the Civil War was very miserable. We have lots of accounts of troops sleeping in fields during the winter, waking up soaked and frozen, we have stories of soldiers having to do, having to go for a long time on very little food and of course, if you're injured as a soldier, that often leads to serious life altering injuries in a way which modern medicine that might be able to prevent. So there's a collective letting off of steam mixed with a religious fervour, and amidst the looting and destruction the soldiers come across the medieval mortuary chests, which I believe the originals are now displayed in the very, very impressive, permanent exhibition of the Cathedral, I believe it's the Kings and Scribes.

Julie: Yeah, Kings and Scribes exhibition, which is quite amazing.

Alex: I would recommend it to anyone, its absolute it's a real, real joy. And these medieval mortuary chests are effectively boxes housing the bones of some important figures, Kings and Queens, bishops of Anglo-Saxon and early Norman, England. The soldiers pull these down, they smash up the boxes until the bones are all mixed. And some, there's a wonderful image, which is that the soldiers, when they managed to get the hands on, on clerical garb, the vestments of the clergy and they ride off into the night wearing them, as a sort of act, act of mockery.

So, the cathedral is very badly damaged this in this, as, as might be expected. And the west window, I think is a very elegant Memorial to that because you can see these tiny fragments of what this medieval window must've looked like for hundreds of years and completely destroyed in a couple of hours of a rampage. It's very fascinating.

Julie: Yeah, absolutely. And I do like the fact that it's, as you say, it's, it's a Memorial that to it. So it's acknowledging the fact that this happened and we're not going to go back to the past necessarily. We’re just going to recognise that it happened, and this is what we're going to do. And it's, it's absolutely stunning. So if any of our listeners have the chance to go through Winchester Cathedral, I do recommend it. It's just, it takes the breath out of you.

Alex: I'd love to know. I'd to know exactly how it was remade, the tradition seems to be that the glass was, was collected and kept. And after the restoration of King, of King Charles's son, Charles, the second, the, window was sort of remade. There's this like weird, kaleidoscope or mosaic of all these fragments. I'd love to know who housed all the glass for 11 – or no, what would it be 15 or 16 years – and I'd love to know how it was remade.

Julie: But you mentioned Charles's son Charles, the second. So we've talked a lot about the Civil War and ordinary people and how they reacted, but can you, can you talk about the role of King Charles, the first and the second and what, what happened and how are they linked to Hampshire?

Alex: Yeah, sure. So Charles, the first was the king at the time of the Civil War breaking out and when we talk about the Civil War, if we're being extremely pedantic what we're talking about is the British Civil Wars, and there are three of them: - 1642 to 1646, 1648, and then 1650 sort of then sort of a later one ending in 1651. So there are actually three, three wars. Charles fights the first one and looses. The decisive battle was the Battle of Naseby on the 14th June 1645.

And after Charles was defeated, after a bit of toing and froing, and the story is quite complex - I'll just simplify it a bit - he eventually ends up in captivity on the Isle of Wight at Carisbrooke Castle where he - it's all very exciting - he seems to have carried off an affair with a royalist agent who was in disguise as a washer woman in the castle. There's a very interesting new book about female spies, especially in the early modern period, by a historian called Nadine Akkerman, and from his captivity, he presided at his forces in England, fought the Second Civil War, which was a real turning point for, the relationship between King and Parliament. Before then it's the basic tenor of things had been being a King and Parliament, well, Parliament wanted to try and come to some sort of treaty with the King. The details of which could never really be worked out because both sides had different ideas about what a peace would look like.

After the Second Civil War, there is a very strong current, especially within the new Parliament's army called the New Model Army, which thinks of Charles as a man of blood, someone who can't be trusted to ever rule over peace. He'll just try and he'll just try and keep on fighting wars until he wins. There's also a religion – again, there’s a religious motive, which is the idea that Charles is sort of a curse on the nation. The man of blood comes from a, a biblical passage about someone who needs to be killed to expiate the nation of his sin in spilling blood. But Charles, after, after that, Charles was eventually brought to a trial, and executed on the 30th of January 1649. Interestingly he does seem to have stopped in Winchester on his way to his trial as you can imagine, it must've been some bit of a mournful, a mournful trip on his way to, on his way to be tried for his life. And there wasn't, there does seem to have been some sort legend that the son of the warden of Winchester college at the time tried to carry out some sort of scheme to rescue him though – this is only mentioned in passing and of those very annoying documents where you wish the author had spent a bit more time on the story.

With Charles dead the throne immediately passes to his son, Charles the second, who is recognized by his supporters. Meanwhile, Parliament declare a Republic quite shortly after the execution of Charles the first and thus begins the next period of the wars, which ends with Charles the second being defeated at the Battle of Worcester in 1651, at which point he famously runs along the modern day Monarch’s Way, stretching down to the south coast to full of lots of adventures, including hiding in trees, sort of run and sort of, you know, sort of, lots of escapades to avoid detection. And he goes off into exile and bar a few scares, most historians think that after that Battle of Worcester, the cause of the monarchy in England is militarily more or less dead. There are some scares later on, but that does seem to have been sort of the final hurrah of the Civil Wars with royalism as a significant presence.

And so England has a long, long period known as the interregnum, the period without a king until Charles the second returns in 1660s. Well, everyone says he was joyfully received and everyone was very happy, which, which might just be everyone seeing which way the wind was blowing as the king returns with no serious opposition, Oliver Cromwell having died and Richard Cromwell, his son, having to abdicate and flee. Richard Cromwell, incidentally who lived in Hursley three miles, we'll set with that, be three miles south of Winchester. And ironically, ironically, he's buried, I've always found this very, very coincidental is, Richard Cromwell is buried in the parish church opposite of which is a pub called the King's Head, which considering his father was instrumental in chopping off a King's head. It seems an interesting coincidence.

Julie: It does, doesn't it? Oh, that's actually, I've noticed that pub and it's a great name, but I did not know that he was buried across there. Is there any other stories or anything else that you think we should know about the Civil War in Hampshire?

Alex: I think, I think there's plenty of, amazing little stories. I mean, one, one thing I've always found quite entertaining is that the church of St Swithun’s in Winchester, was let as a residence during the interregnum, but it let to one Robert Allen and the quote goes, “his wife delivered of children at one end of the church and a hog sty was made at the other end of the church”. So I think it's a curious world during the Civil Wars and afterwards where many very traditional received facts were, were challenged or overthrown by circumstance and people had to react in very odd and unexpected ways.

There's also, and I think there's also so many very interesting little fragments of the Civil War left in the material landscape of places. So I think for example, Basing House, bears the scars of the siege, which, which Cromwell oversaw. Romsey Abbey, I think has a huge number of muskets and cannonball wounds. And I think, I think Alton church, I believe has similar sort of marks of battles and so on from when a royalist commander had his last stand inside the church. So lots of, I think if you're ever in any place of worship in Hampshire and you notice what looks to be a weird looking mark or hole, the chances are it's like from Civil Wars and it might have an interesting story.

Julie: My thanks to Alex Beeton for his insight into the Civil War and to Aisha Al-Sadie for creating such a vivid tale. And if you do visit any churches and see a mark or hole that you think might be from the Civil War era, then do let us know using social media as we'd love to see it.

If you want to listen to more stories from Aisha and Alex then do check out our podcast catalogue on our website. Thank you for listening.

Outro: We hope you enjoyed listening to today’s episode. If you would like to find out a little bit more about what we’ve been talking about, then please visit the website, www.winchesterheritageopendays.org, or click on Hampshire HistBites, and there you’ll find today’s show notes as well as some links to more information.